If you were to guess at the persona of the country’s longest serving legislator you might come up with someone like Bill Clinton. Gregarious, smooth, glib, manipulative and ruthless when he thought he needed to be.

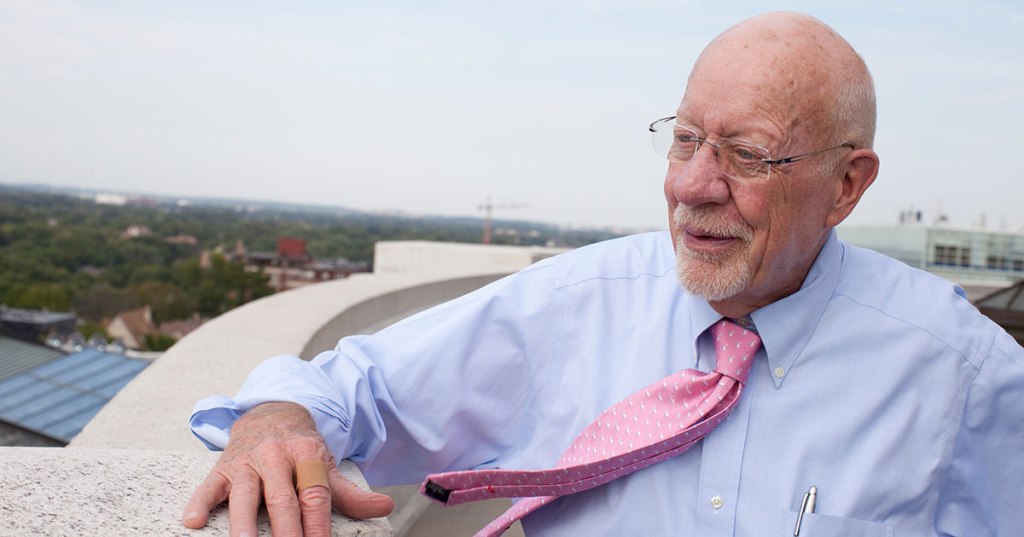

It turns out that the man who holds the national record for legislative service, at 64 years, is Madison’s Fred Risser — who is none of those things. Risser is, if anything, a somewhat shy person who can be awkward in social settings. He’s friendly and gracious, but hardly a backslapping good old boy. He was masterful in debate on the floor of the state Senate, but he can be halting when called upon to deliver extemporaneous remarks in a casual setting. And that stereotype of the pol who never forgets a face and a name? Well, that’s not Fred.

And yet, Fred Risser served longer by far than anyone in any legislature in any state in the history of the United States. He was elected to the state Assembly in 1956, moved up to the state Senate in 1962, and he finally retired in 2020. Go figure. Well, actually, let’s try to figure it out.

We can start with Risser’s new autobiography, Forward For the People, published this summer by the Wisconsin State Historical Society Press. Risser wrote the book with longtime Madison journalist and author Doug Moe. No doubt Moe prompted Risser with reporter’s questions and organized his responses, but the prose sounds like Risser. Perhaps a little more relaxed and informal, but it’s still Fred’s voice.

I should know as — full disclosure — my wife, Dianne, worked for him for 16 years. When she took the job we talked about this being a temporary gig as Fred would surely retire before she did. Dianne retired as his chief of staff in 2013. Fred outlasted her by eight years.

He also outlasted generations of politicians who wanted his job. Fred was cast as too old or somehow ineffective by a succession of serious contenders, starting with Michael Christopher in 1992, Stu Levitan in 1996, and Carol Carstensen in 2000. None came close to beating him.

They didn’t succeed because Risser respected them all. He took them seriously and he worked hard — tirelessly knocking on doors — to meet their challenge. Risser never made the mistake of condescending to his opponents whether in an electoral contest or in the Legislature. He still counts many of his former adversaries as friends.

In fact, what struck me most about his book is that, after over six decades in public life, Risser doesn’t really have a bad word to say about anyone, save Joe McCarthy and Scott Walker. When McCarthy died in 1957, Risser’s first year in the Assembly, Fred made it a point to absent himself when the Republican-controlled Legislature voted on a resolution honoring his life. And as for Walker, while he doesn’t explicitly say it this way in the book, Risser told me that of the 13 governors he worked with he counted only Walker as a chief executive who really did not have the best interests of the state at heart. Politics is a tough business and things often get personal whether you want them to or not. And yet Fred Risser found a way to stay above the muck. He’s a fighter, but he’s never been a hater.

Even if you think you know all you care to know about Risser (and you don’t — you’ll be surprised by some things), his book covers over six decades of Wisconsin political history in a brisk, almost breezy manner. The book is filled with anecdotes and brief profiles of the famous and obscure from Madison, state and even national politics. I read its 200 pages in two sittings and didn’t feel like I broke a sweat.

Readers will be especially interested in his account of the Act 10 fight and the 14 Senate Democrats’ flight to Illinois to slow the bill. That was a high profile battle, but Risser led one lonely fight after another on other progressive issues, some gaining momentum (like his push for seatbelts in cars and a smoking ban in bars and restaurants) over the long haul and others (like his repeated attempts to repeal what was then a moot 1849 anti-abortion law after Roe v. Wade was decided) that came to a dead end. Any Madison mayor should be grateful for his decades-long service on the Building Commission where, he tallies, in the decade of the 1990s alone he delivered some 20 new state and campus buildings worth $370 million.

One thing Risser never takes on directly in this book is how it happened. How did a guy who had politics in his blood — he was the fourth generation of his family to serve in the statehouse — but was not a natural politician by any means, end up serving longer than anyone else?

We don’t get a straightforward answer, but maybe you’ll find it buried throughout the text. At the end of the first chapter he writes, “For all those years, I got up in the morning eager to see what the day would bring. I believe an enduring optimism is necessary for extended public service. You need to think you can help change things for the better. I see it in my great-grandfather who wrote letters home from the Civil War, and on down the line. A hopeful mindset. Like much else, it’s in my blood.”

These days, with so many politicians fueled by venom, it might be refreshing to look back on one who ran a marathon fueled by hope.

Risser and Moe will talk about their book tonight, Sept. 24, 6 p.m., at the Madison Central Library.

A version of this piece originally appeared in Isthmus.

I believe it was Cathy Christensen and not Carol Carstensen who ran against Fred in 1980.

LikeLike

Carstensen ran against Fred in 2000.

LikeLike