What do you own if you own land? Conservatives might answer, “everything.” Liberals might be more inclined to say that you are stewarding a public resource. The answer to the question of just what it is that you own is constantly evolving.

By Harvey M. Jacobs

This is the third in an occasional series on environmental issues from Harvey Jacobs, retired UW professor and Professor Emeritus, Radboud University Nijmegen. The first is titled Searching for a Responsible Localism, and posted on February 2nd; the second is titled Is There Too Much Regulation?, and posted on February 15th. This post on land ownership and property rights is in three sections; it will conclude with a subsequent post.

Two Views of Land and Private Property Rights in America

This land is your land, this land is my land . . . This land was made for you and me.

Woody Guthrie – This Land is Your Land (1944)

This land is my land, it isn’t your land . . . If you don’t get off, I’ll blow your head off

David Pratter (date unknown) – This Land is My Land (This Land is Your Land parody)

Section 1 – An Ambiguous Colonial-Constitutional Legacy

Since the early 1990s, actually since the 1960s, conservative and liberals have been fighting about what it means to own land. What are my rights in my land, what are society’s rights in my land (do they even have any), do I have social responsibilities when I own land? These and related questions have fueled both the rise of the environmental movement and the so-called property rights movement.

We have been fighting about who should own America, and what ownership even means, since the time of America’s ‘discovery’.

Of course, America’s land had long been settled and owned by its native inhabitants, but those claims were ignored and pushed aside by the Spanish, French, Dutch, British, and others who came across the Atlantic. And over the ensuing hundreds of years claims by other non-whites – former African-American slaves, those of Hispanic descent in the Southwest, those of Japanese descent in the West, among others – have also been wrongly ignored and pushed aside.

Acknowledging all this, there are still important things to reflect on about the social conflict over property and ownership.

High school students are often taught that what motivated European settlers to the American colonies were those freedoms embodied in the first amendment of the Bill of Rights – speech, religion, assembly, and the press. While this is not untrue, historians of all stripes agree that as large, if not larger, motivator for many was the promise of land. The chance to own land was an opportunity largely unavailable to regular people in Europe; America was the land of opportunity – literally.

And America’s founders realized this. John Adams, the second American president, Thomas Jefferson, the third president, and James Madison, the fourth American president, left us with stirring words and ideas about how central land ownership – the right to private property – was to the founding of the new government. For Adams the right of property was central to freedom. For Madison, the very point of government was to secure the right to property. For Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence, small-scale, independent landowners – yeoman farmers – provided the very foundation for both a democratic political and social system.

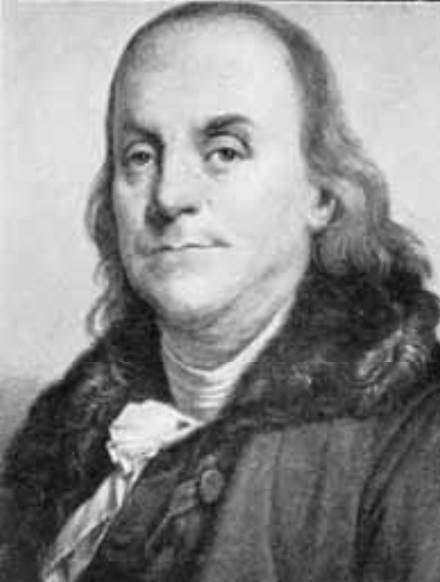

But what is often not acknowledged is that the founders were not of one mind about this matter. Among them there were strong and influential dissenting voices. The most dramatic of these was that of Benjamin Franklin, the inventor, publisher, and colonial ambassador to France during the war of independence. For Franklin (and others) land and property were social creations and had to bend to society’s needs whatever those needs were.

The founders’ resolution of their disagreements was messy. In 1776 The Declaration of Independence did not promise a right to land. Americans are promised “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” But Jefferson took this phrase from political philosopher John Locke who had argued that it should be life, liberty, and land. Jefferson had wanted the Declaration to say just this, but others disagreed.

Eleven years later, in 1787, The Constitution was drafted. It too says nothing about an individual’s right to land. It wasn’t until 1791 that the Bill of Rights was adopted and finally something was said. But even this is ambiguous. The final twelve words of the Fifth Amendment state: “nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.”

In this phrase the Constitution recognized the existence of private property, but allowed this property to be taken by government, if the taking was for a public use, and the owner was given just compensation. But none of the components of the phrase were defined: not private property, not taken, not public use, not just compensation.

And it is this lack of definition which has helped fuel the ensuring centuries of social conflict.

Section 2 – Conflict in the Early 20th Century

The ambiguous colonial-Constitutional legacy was of little consequence through most of the 1700s and 1800s. Continental expansion was America’s land agenda for those years. This was accomplished through treaties with European powers and Mexico, purchases from European powers, wars, and the continual displacement of native peoples from their traditional lands, and then again from the lands they were forcibly resettled to. The national government actively pursued a policy of settlement through programs like the 1862 Homestead Act.

But by the turn of the 20th century America was changing. We were becoming an industrialized and urban country. At the Chicago Exposition of 1893, Wisconsin born University of Wisconsin historian Frederick Jackson Turner declared that with the end of the 19th century the American frontier was closed. As Americans urbanized and the economy industrialized issues of private property came into sharper focus. Cities boomed – Chicago, Cleveland, St. Louis, New York, etc. And as they did, they responded by passing regulations for the use of private land (see my my February 15 post: Is There Too Much Regulation?). Landowners could no longer just do what they wanted with their land.

Legally this wasn’t a problem. The takings clause of the Bill of Rights was about the physical taking of land by government for roads, hospitals, schools, etc. It was not about the right of government to regulate. As late as 1915 the U.S. Supreme Court said state and local governments could broadly use the power of regulation without any limitation. As long as individuals were left with some rights in land, government regulation was valid. So governments regulated and regulated. And as they did, it eventually created a problem.

In 1922 the Court decided a Pennsylvania case in which the State had regulated how a coal mining company could use their mining rights. The company did not own all the land on which they mined, just the right to mine the coal. The state regulation prevented their mining because it caused the collapse of the land over the mine, land owned by someone else. The coal company claimed that their private property had been taken under the terms of the Fifth Amendment, and that they were owed compensation (or an annulment of the regulation). The Court agreed. At this moment, a new idea entered American law and governance – regulatory takings. That is, it is the idea that a regulation can be equivalent to a physical taking if a regulation goes‘too far’. When this is the case, then an owner of the land (or the rights) being regulated can claim for compensation.

The practical impact of this new doctrine was actually quite minimal for much of the next fifty years. But it underlay the intense social conflict that emerged with the environmental movement of the 1960s and 1970s, as all levels of government undertook an intensive period of regulation.

Section 3 – The Rise and Impact of the Private Property Rights Movement

Land is a real thing. You can go out and step on it, pick it up, plant into it. Yet land is also a legal thing which western law conceptualizes as a bundle of rights. These rights are of two sorts. One relates to the physical nature of land, and one relates to what you can do with your land.

What do you own if you own land? In theory complete ownership can mean that you own the soil, the water on and below it, the minerals below it, trees and other plants on it, the air above it, and perhaps the animals upon it. What can you do with your land? You can use it, rent it, give it as a gift, sell it, and importantly control access to it. (As Simon Winchester shares in his 2021 book Land, “the very concept of ownership reduces itself to one simple and popularly accepted fact . . . you have the right to call the police to throw anyone else off what the title documents say belongs to you”; emphasis in original).

What is fascinating about this overall concept is that what you may do with your land applies not only to the land as a whole, but to all the rights in your bundle. So you can sell your mineral rights, you can lease your water rights, you can gift your (future) use rights (conservation easements), you can selectively manage trespass (e.g. during hunting season), for free or for a fee, all while continuing to own the land.

And what is also usually true, is that these rights in land are of unequal value. If you own land in coal, oil, or gas country, then the most valuable right is likely to be the mineral right. In the American southwest the most valuable right is likely to be the water right. If you own land at the edge of a growing city, then the most valuable right is likely to be the right to intensify land use (to develop the land).

In situations such as these the most valuable right can represent 90+% of the total market value of the land.

Starting in the late 1960s, partially in response to new environmental science and with the active support of the new environmental movement, government at all levels began regulating land as never before. Programs for clean air, clean water, endangered species, farmland, open space, and wetland protection, sustainable forestry, among others, proliferated. As they did, landowners found themselves with more and more constrained options for using their own land. And often these regulations were adopted with limited consideration for the burden they might impose on landowners.

By the late 1980s a counter-movement – the private property rights movement – coalesced. It argued that in line with the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1922 decision many if not most of these regulations went ‘too far’, and as such landowners were entitled to compensation. Why was this true? Because many of these regulations impacted the most valuable rights in the property bundle. So it didn’t matter how many of a landowner’s property rights were unaffected, but how the overall potential economic value of the property had been reduced.

The rhetoric and advocacy of the property rights movement was powerful. By the mid-1990s, 27 of the lower 48 states had adopted one or more versions of so-called private property rights protection laws. These laws were intended to blunt the aggressive regulation of privately owned land. The rapidity of state adoption of these laws shocked the environmental community, as did the fact that some of these states were among the most progressive in land use and natural resource management.

The actual impact of these laws is disputable. But what is not disputable is that the public and policy conversation about land use and environmental management substantially changed in America. Conservatives had pushed back against liberals and found sympathy among many.

Conservatives and liberals now stare at each other across an abyss. For conservatives, private property is just that – private, and with limited exceptions they believed you should be able to do what you want to with it. If the public chooses to regulate land then they believe they are often entitled to compensation. For liberals private property is a stewardship, and it involves a delicate balance of private and public interests, and the cases for compensation are few and far between.

Are these differences irreconcilable? Is there even a space for a moderate position?

Harvey M. Jacobs is a retired professor from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where for over 30 years he taught in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning and the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies. More information about him and his work is available at harveymjacobs.com.

Part of the core of the American Dream since it’s creation is to own property, it’s a social status symbol, do not infringe on the perceived right to for what our society considers the opportunity for prosperity and success, as well as an upward social mobility for the family and children that’s achieved through hard work in a society with few barriers, which is the core of the American Dream, or there will be serious societal problems. Yes these differences are reconcilable as long as one side of the chasm is not perceived as literally trying to strip the other side of the rights they’ve had for many generations. Great care should be taken when heading down the very slippery slope of infringing on the rights of individuals in the United States.

The United States of America is not a social commune and those that appear to be pushing us towards that end need to get off their pompous high horses and stop trying to destroy the United States as it is. This push to turn the United States into their alternate reality social utopia is not achievable goal as long as there are intelligent critically thinking human beings that have the free will to choose their path in life.

All that said; we all need to be good stewards of the planet and its resources for the good of the planet and the entire human race.

LikeLike

Steve,

Thank you for your comment.

In my next post I attempt an answer to my question ‘are these differences irreconcilable’?

I will be very curious to see if you agree or disagree with how I try to move this discussion forward.

Fundamentally, I agree with both of your points: 1) there needs to be respect for the acquisition of private property and what it means to so many, and 2) we need to be good stewards.

Harvey Jacobs

LikeLiked by 1 person